The International Center for Appropriate and Sustainable Technology (iCAST) helps communities use local resources to solve their own problems. I’ve been a fan of iCAST’s approach of teaching people how to fish (or, in this case, how to apply sustainable technologies) rather than giving away fish since I first encountered them at a conference in 2006. Last week, they took advantage of some of their own local resources (namely the fact that the DNC was in Denver) to organize a luncheon with a panel of nationally recognized speakers, any one of whom would have been enough to draw a crowd alone, and asked them to speak about how coping with Climate Change will impact the poor.

The speakers were Daniel Esty, co-author of Green to Gold

Should Investors Worry About the Poor?

Stereotypically, business and investors do not care about the plight on the poor. Like most stereotypes, it only has to be true if we choose to live down to it. Many argue that socially responsible investing can lead to superior returns, and have studies to support this conclusion, but the mutual fund track record shows mixed results. I personally ascribe underperformance of socially responsible mutual funds to high fees and unsuccessful active management. Moral responsibility does not absolve the investor from the need of doing good research, but my anecdotal experience leads me to the belief that at least among individual investors, many act as if moral investing is a substitute for due diligence. Addressing Climate Change need not come at the cost of profit (Walmart came to energy efficiency from the profit motive, not an environmental ethic, as Ms. Christensen pointed out.)

That said, it’s an equal fallacy to assume that financial due diligence absolves us of moral obligation. I’m not here to tell you what your moral obligations are, but for many it will probably include making sure that the most vulnerable people do not bear the bulk of the cost of decarbonizing our energy supply. On a more cynical note, it’s a lot easier for people to accept large profits if more people are helped than harmed in the process of making them. I attended the luncheon with the hope that I would gain some ideas on specific types of companies which are both addressing both the problem of Climate Change and of poverty.

Climate Change and the Poor

The good news is that there is considerable potential for leapfrogging, with off grid or microgirds powered by solar or wind often being the cheapest way to bring electricity to remote locations which never had it before. The bad news is that although such projects often bring tremendous benefits to the people in need, and carbon emissions are reduced as electric light displaces oil lamps or candles, the small scale of such projects and the limited financial resources of their users mean that such projects can seldom be completely self-financing.

Yet the rural poor are not the only ones who will benefit from switching to renewable sources of energy. Since these projects bring reductions in carbon dioxide and other pollutants, a carbon trading system could help to bridge the gap between need and ability to pay. According to Ms. Christensen, current carbon prices are still too low to bridge the gap, in large part due to uncertainty in the quality of offsets on offer. If the buyer is uncertain that the project producing the offsets purchased would have happened without the sale of offsets, he will be less willing to pay as much for each offset. This is the much discussed problem of additionality.

Another problem is moral hazard. In an unregulated environment where there are buyers of carbon offsets, a company will have an incentive to plan a new factory using less efficient processes, or even intentionally emit more of a potent greenhouse gas such as HFC-23, than they might on purely economic grounds, in order to receive a payment to later upgrade the factory to use the more efficient process they might have used anyway.

Raising the Price of Carbon, and Enabling the Poor to Sell

There are many efforts underway to improve and certify the quality of carbon offsets on the market. Organizations such as Green-e certify offsets to high standards, and allow retailers to place their logo on certified offsets and Renewable Energy Credits, but the very proliferation of such efforts speaks to the difficulty of the combined certifying additionally without providing perverse incentives.

A much better solution would be global carbon emissions regulation. By providing a mandatory cap (even a rising one) for all countries, the total number of offsets sold would be limited to the amount by which emissions were below that cap. This would provide certainty of additionality, and also remove the perverse incentive to emit more in order to receive later payments to cut emissions.

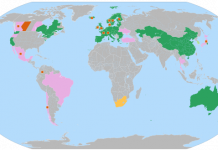

The prospects for a truly global treaty to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, referred to by Mr. Esty as "

;Kyoto II", are mixed. He believes that China would be willing to sign up to a truly global agreement (although they would definitely negotiate hard to get a relatively forgiving emissions quota,) but that India does not yet feel the necessary urgency which would induce it to join such a regime. Given the size and growth of these two emerging economies’ emissions, both would be necessary signers to persuade smaller emerging economies to join.

A global treaty, by both creating demand for carbon offsets, and by providing more certainty as to the quality of those offsets, would go a long way towards increasing prices and making combined poverty reduction/carbon reduction projects economically viable. It’s my hope that the benefits of self-sustaining poverty reduction schemes run by for-profit businesses, and made economic by carbon offsets could be enough to induce large, poor, but rapidly industrializing countries like India and China to join a global carbon regulatory treaty.

Climate Change and Poverty Reducing Investments

Until we have strong, global carbon markets, we should look for investments which help bring them about. North American investors can now buy an American Depository Receipt for Climate Exchange PLC (CXCHY.PK) the parent of the Chicago Climate Exchange (CCX). However, the carbon contracts traded by CCX have been frequently criticized on the basis of lack of additionality. On the other hand, the CCX already allows different sorts of offsets to be traded, and the offsets most criticized for additionality are those for the carbon sequestered by low till farming, since there are documented instances of farmers who already follow this helpful practice being paid for what they had already been doing. An even more serious criticism of no-till farming is that the science behind the measurement of carbon sequestration is in doubt. If our priority is solving Climate Change, the additionality and certainty of carbon sequesteration is of great concern, but if we are pursuing the dual goals of poverty reduction and carbon sequestration, then the lack of additionality is a minor concern, since there is always uncertainty in what is truly "additional." After all, even if a farmer had been practicing no-till for years and only now is receiving payments, those payments may be enough to keep him in business and keep his land from being plowed by a less progressive farmer.

But how will Climate Exchange PLC fare when a global carbon trading system is finally established? The signs do not seem good. At the moment, CCX’s advantage in the carbon market seems to be that they both define the contract and provide a platform for trading it. If governments step in to define carbon contracts by regulatory fiat, CCX will only have the advantage of incumbency, something of dubious value when the trading is in a new contract.

A better investment would be a company which is alredy in the business of developing high-quality carbon offsets, that is, starting projects which reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and would not have happened without offset payments. Such companies would likely be able to focus their efforts on developing contracts which could be sold into any well thought out regulatory regime. One I did find was Veolia Environmental Services (NYSE:VE), which sells offsets from landfill gas projects. This is admittedly a small part of their business, yet their other businesses, focused on water, waste, energy efficiency, and transit are all sectors likely to do well as we confront the reality of Climate Change, and also sectors of concern to the world’s poor.

DISCLOSURE: None.

DISCLAIMER: The information and trades provided here and in the comments are for informational purposes only and are not a solicitation to buy or sell any of these securities. Investing involves substantial risk and you should evaluate your own risk levels before you make any investment. Past results are not an indication of future performance. Please take the time to read the full disclaimer here.